Acute diarrhea can feel like a sudden storm that knocks you off your feet, and for many people it also awakens a hidden sensitivity to dairy. If you’ve ever wondered why a bout of stomach upset makes milk feel dangerous, you’re not alone. Below we untangle the biology, point out practical steps, and show how the two conditions often walk hand‑in‑hand.

Quick Take

- Acute diarrhea is a rapid, short‑term increase in watery stools (usually < 14 days).

- Lactose intolerance is the inability to fully digest lactose because of low lactase activity.

- Severe diarrhea can damage the small‑intestinal lining, causing a temporary, or secondary, lactase deficiency.

- Symptoms often mimic osmotic diarrhea: bloating, cramps, and watery bowel movements after dairy.

- Rehydration, a low‑lactose diet, and probiotics help break the cycle.

What is Acute Diarrhea?

Acute diarrhea is a sudden onset of frequent, watery stools lasting less than 14 days, typically triggered by infection, food poisoning, or a rapid change in diet. It is characterized by a high stool volume, possible fever, and the risk of dehydration. In most healthy adults, the condition resolves on its own, but the rapid loss of fluids and electrolytes can stress the gut lining.When the lining of the small intestine is bathed in excess water and inflammatory mediators, its brush‑border cells can become temporarily impaired. This is a key bridge to lactose intolerance, because the same cells house the enzyme lactase.

Understanding Lactose Intolerance

Lactose intolerance is a condition where the body cannot fully break down the milk sugar lactose due to insufficient activity of the enzyme lactase enzyme. When lactose remains undigested, it ferments in the colon, pulling water into the lumen and creating classic symptoms: bloating, gas, cramps, and loose stools.There are two main flavors of lactose intolerance:

- Primary (genetic) lactase deficiency: a gradual decline in lactase production after childhood, common in many Asian, African, and Indigenous populations.

- Secondary (acquired) lactase deficiency, where an illness or injury damages the intestinal lining, causing a temporary dip in lactase activity.

It’s the secondary type that often rides shotgun with acute diarrhea.

How Acute Diarrhea Can Trigger Secondary Lactase Deficiency

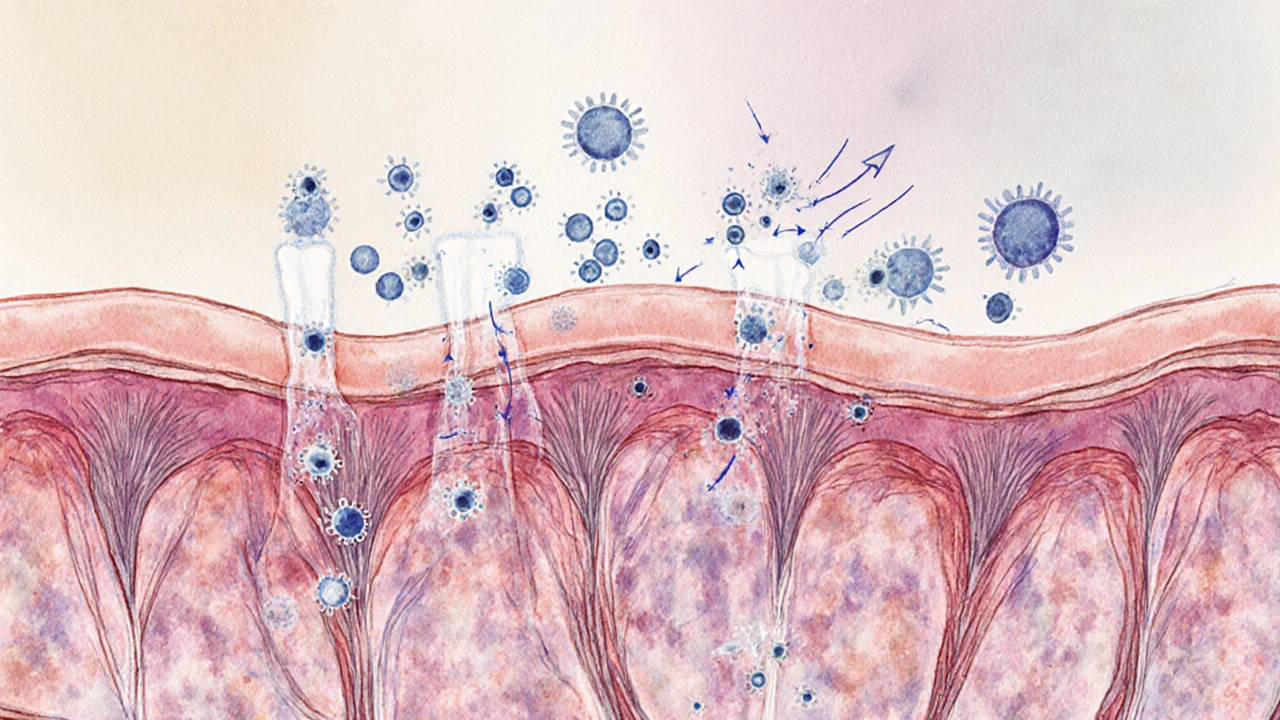

The gut’s lining is a delicate carpet of villi and microvilli, each studded with lactase enzymes. During an acute diarrheal episode, several things happen:

- Infection or irritant agents (e.g., Campylobacter, norovirus, or a high‑fat meal) inflame the mucosa.

- The inflammatory cascade releases cytokines that cause the enterocytes to shed.

- Loss of enterocytes means a loss of lactase, creating a temporary secondary lactase deficiency.

Because the deficiency is acquired, it usually resolves once the gut heals-anywhere from a few days to a couple of weeks. However, during that window, any dairy you consume can aggravate the diarrhea, making the problem feel circular.

Osmotic Diarrhea: The Common Pathway

When undigested lactose reaches the colon, it acts as an osmotic agent, pulling water into the bowel lumen. This creates osmotic diarrhea, a subtype of diarrhea defined by the presence of a non‑absorbed solute (like lactose) that draws fluid. The pattern is clear:

- Symptoms improve when you stop consuming the offending carbohydrate.

- Stool osmolar gap is typically > 50 mOsm/kg, confirming an osmotic driver.

In contrast, secretory diarrhea (often caused by toxins) continues regardless of diet. Recognizing the osmotic nature helps you target the right treatment: cut the lactose, rehydrate, and support gut healing.

Managing the Double Trouble

Breaking the cycle involves three pillars: rehydration, diet, and gut support.

Rehydration

Loss of fluids can happen quickly. The gold standard is an oral rehydration solution (ORS) that combines water, sodium, potassium, glucose, and citrate in a specific ratio to maximize absorption. For most adults, a homemade version-1 liter of clean water, 6 teaspoons of sugar, and half a teaspoon of salt-does the trick. Commercial ORS packets (often sold in pharmacies) are calibrated to WHO guidelines.

Dietary Adjustments

While you’re recovering, keep the gut calm:

- Choose low‑lactose or lactose‑free dairy (lactose‑free milk, hard cheeses, Greek yogurt).

- Embrace the BRAT diet (bananas, rice, applesauce, toast) for easy digestion.

- Avoid high‑FODMAP foods (certain fruits, honey, wheat) that can mimic lactose symptoms.

Once stools normalize, you can gradually re‑introduce small amounts of dairy to test tolerance.

Probiotic Support

Beneficial bacteria can accelerate mucosal repair and restore a balanced gut microbiota. Strains such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Saccharomyces boulardii have documented efficacy in reducing the duration of acute infectious diarrhea. A daily dose of 10‑20billion CFU for 5‑7 days can help shrink the inflammatory response and promote villus regrowth, indirectly boosting lactase activity.

Primary vs. Secondary Lactase Deficiency: A Quick Comparison

| Attribute | Primary (Genetic) | Secondary (Acquired) |

|---|---|---|

| Cause | Age‑related decline in lactase gene expression | Inflammation or injury to the small‑intestinal mucosa |

| Onset | Usually after weaning, gradual | Sudden, coincides with diarrheal episode |

| Duration | Often lifelong | Temporary, resolves as mucosa heals (days‑weeks) |

| Management | Low‑lactose diet, lactase supplements | Address underlying cause, rehydrate, probiotics, gradual dairy re‑introduction |

When to Seek Medical Help

Most cases settle within a week, but watch for red flags that signal severe dehydration or an underlying infection:

- Persistent vomiting or inability to keep fluids down.

- Stools that are bloody, contain mucus, or have a fever>38.5°C.

- Signs of dehydration: dry mouth, dark urine, dizziness, or a rapid pulse.

If any of these appear, a healthcare professional can order stool cultures, test for C.diff toxin, or prescribe antibiotics when appropriate.

Related Concepts and Next Steps

Understanding the link between acute diarrhea and lactose intolerance opens doors to broader topics that often pop up in health blogs:

- Foodborne pathogens: bacteria, viruses, or parasites that start the diarrheal cascade.

- FODMAP diet: a structured low‑carbohydrate plan that helps identify triggers beyond lactose.

- Antibiotic‑associated diarrhea: a special case where antibiotics disrupt the gut microbiota, sometimes leading to secondary lactase deficiency.

- Dehydration management: the science of electrolyte balance and why plain water isn’t enough.

After you’ve cleared the acute episode, you might explore:

- Testing for primary lactose intolerance with a hydrogen breath test.

- Learning how to read nutrition labels for hidden lactose.

- Trying fermented dairy (yogurt, kefir) that contain live cultures, which can aid digestion.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a single bout of diarrhea cause permanent lactose intolerance?

Usually not. Most people develop a temporary, or secondary, lactase deficiency that resolves as the intestinal lining heals. Permanent intolerance is typically genetic.

How long does secondary lactase deficiency last?

It can last from a few days up to two weeks, depending on the severity of the inflammation and how quickly you rehydrate and nourish the gut.

Is it safe to take lactase supplements during diarrhea?

Lactase pills can help if you need to consume dairy for nutrition, but they won’t treat the underlying fluid loss. Prioritize ORS first, then add supplements if needed.

What’s the difference between osmotic and secretory diarrhea?

Osmotic diarrhea is driven by undigested solutes (like lactose) pulling water into the gut; it improves when the offending food is removed. Secretory diarrhea is caused by toxins or hormones that force the intestine to secrete fluid, persisting regardless of diet.

Can probiotics speed up recovery from acute diarrhea?

Studies from the WHO and several gastroenterology societies show that specific strains (e.g., L. rhamnosus GG) can reduce the duration of infectious diarrhea by about 24‑48hours and help restore lactase‑producing cells.

Should I avoid all dairy after a diarrheal episode?

Start with low‑lactose options (hard cheese, lactose‑free milk) and monitor symptoms. If you feel fine, gradually re‑introduce regular dairy to test tolerance.

Stay hydrated and you’ll be fine.

The gut inflammation you get from a nasty bug isn’t just a minor inconvenience; it literally strips away the brush‑border enzymes that digest lactose. That’s why dumping dairy during an episode feels like the only sane choice. It’s not a coincidence, it’s biochemistry in action. People who ignore this end up suffering longer bouts of osmotic diarrhea. And don’t tell me it’s just “habit” – the lactase loss is real and measurable. The moment you rehydrate and give the epithelium a break, the lactase levels climb back. Skipping the probiotic step is a rookie mistake; those microbes accelerate villus healing. So, respect the temporary lactase dip and avoid dairy until your stools normalize.

I’d say the best approach is to start with low‑lactose options like hard cheese or lactose‑free milk while you’re re‑covering. It’s a simple switch and it’ll keep your calcium intake up. Also, the BRAT diet is recccomended for a few days – bananas, rice, applesauce, toast – easy on the gut. When you feel better, try a tiny splash of regular milk and see how you react. If no cramping, you’re probably back to normal lactase activity.

Hey folks, just remember to sip ORS first – water alone won’t cut it 😊. After you’re re‑hydrated, you can slowly add a bit of lactose‑free milk to keep your nutrients up. Keep it simple and listen to your body.

In my experience, a gentle re‑introduction of dairy after the diarrheal phase works well. Use yoghurt with live cultures – they help rebuild the gut flora. Also, don’t forget to monitor for signs of dehydration; sometimes people ignore the subtle dryness.

Let’s be honest, the pharmaceutical industry doesn’t want you to know that most acute diarrheas are self‑limiting if you just manage the electrolytes correctly. The push for over‑the‑counter anti‑diarrheal meds is a profit scheme that masks the real solution: proper rehydration and a temporary lactase break. Trust the science, not the marketing.

Everyone’s too quick to blame dairy when the real culprit is a hidden pathogen. The way the media frames “lactose intolerance” after an infection is a diversion tactic. Wake up – it’s the gut‑brain axis being manipulated by undisclosed experiments. Stop buying the narrative and focus on restoring mucosal health with proven probiotics.

Just a note – if you’re using over‑the‑counter oral rehydration salts, check the label for sugar content. Too much sugar can actually worsen osmotic diarrhea. Stick with the WHO‑recommended mix or a low‑sugar formula.

Honestly, the whole “lactose intolerance after diarrhea” craze is overblown. Your gut is a resilient organ that can handle a little lactose even during an upset. If you’re feeling dramatic, maybe it’s just your brain looking for an excuse to avoid cheese.

While the mechanisms described are accurate, it’s worth noting that not every diarrheal episode leads to a measurable drop in lactase activity. Individual variability plays a big role, and some people recover almost instantly.

OMG, the drama of a gut gone wild! 🤯 One minute you’re fine, the next you’re battling lactose demons. 🌪️ Trust the probiotics, they’re the real superheroes in this saga! 🦸♀️

It is essential to emphasize that oral rehydration solutions must contain an appropriate ratio of sodium to glucose to facilitate optimal absorption via the sodium‑glucose cotransporter. Failure to adhere to this formulation may result in suboptimal fluid uptake and prolonged electrolyte imbalance.

I’ve seen patients benefit from tracking their dairy intake in a simple journal. It helps identify the exact point when symptoms reappear, making re‑introduction more precise. Pair that with a probiotic regimen, and recovery can be faster.

One must not overlook the underlying physiological cascade that precipitates secondary lactase deficiency in the wake of an acute diarrheal insult. The mucosal inflammation precipitates enterocyte apoptosis, thereby diminishing the brush‑border enzymatic reservoir, specifically lactase, which is indispensable for the hydrolysis of lactose into glucose and galactose. Consequently, the unhydrolyzed lactose traverses to the colon, where it functions as an osmotic agent, drawing luminal water and engendering an osmotic diarrheal state. It is a misconception to attribute this phenomenon merely to “temporary intolerance”; the temporal aspect is governed by the regenerative kinetics of the intestinal epithelium, which varies among individuals based on nutritional status, age, and comorbidities. Furthermore, the therapeutic armamentarium includes not only oral rehydration solutions but also selective probiotic strains, such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, whose metabolomic interactions facilitate villus restitution and lactase re‑expression. Neglecting these nuances leads to suboptimal clinical outcomes and perpetuates a cycle of misdiagnosis. Therefore, clinicians should adopt a multimodal strategy, integrating rehydration, dietary modification, and microbiome support, while monitoring for resolution of lactase activity through objective testing when appropriate.

Cut the dairy until you’re steady – it’ll stop the loop.

Listen up, crew! The key to breaking this nasty cycle is to hydrate like a champ – think ORS, not just plain water. Then, give your gut a break from lactose; go for lactose‑free or hard cheese while you heal. Add a probiotic daily and watch those good bugs do their magic, rebuilding the villi faster than you expect. Keep a food diary, track how you feel, and re‑introduce dairy slowly – a spoonful at a time. You’ve got this, and your gut will thank you for the smart care you’re giving it!