When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you might wonder: is this really the same as the brand-name version you used to take? The answer lies in two closely linked but very different concepts: bioavailability and bioequivalence. Understanding the difference isn’t just for pharmacists or scientists-it affects your health, your wallet, and your trust in the medicines you take every day.

What Bioavailability Actually Means

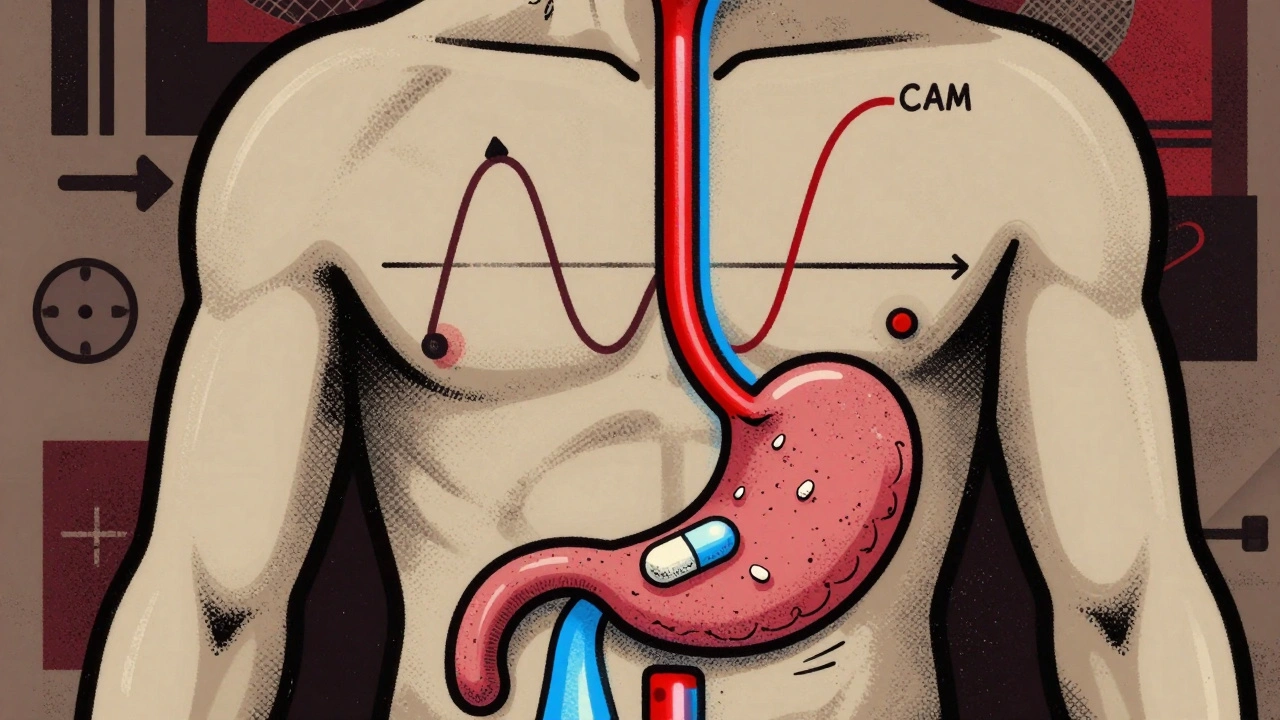

Bioavailability is about how much of a drug actually gets into your bloodstream after you swallow it. It’s not just about the dose printed on the label. If you take a 50 mg tablet, maybe only 30 mg makes it into your blood. The rest? Lost to your stomach, your liver, or your gut lining. This is called first-pass metabolism-your body breaks down part of the drug before it ever reaches your target.

For example, a drug like propranolol has about 25% to 30% bioavailability when taken orally. That means if you take 40 mg, only about 10-12 mg actually circulates in your body. Compare that to if you got the same drug through an IV-100% of it enters your blood right away. That’s why bioavailability is always measured relative to an IV dose (called absolute bioavailability) or compared between two oral forms (relative bioavailability).

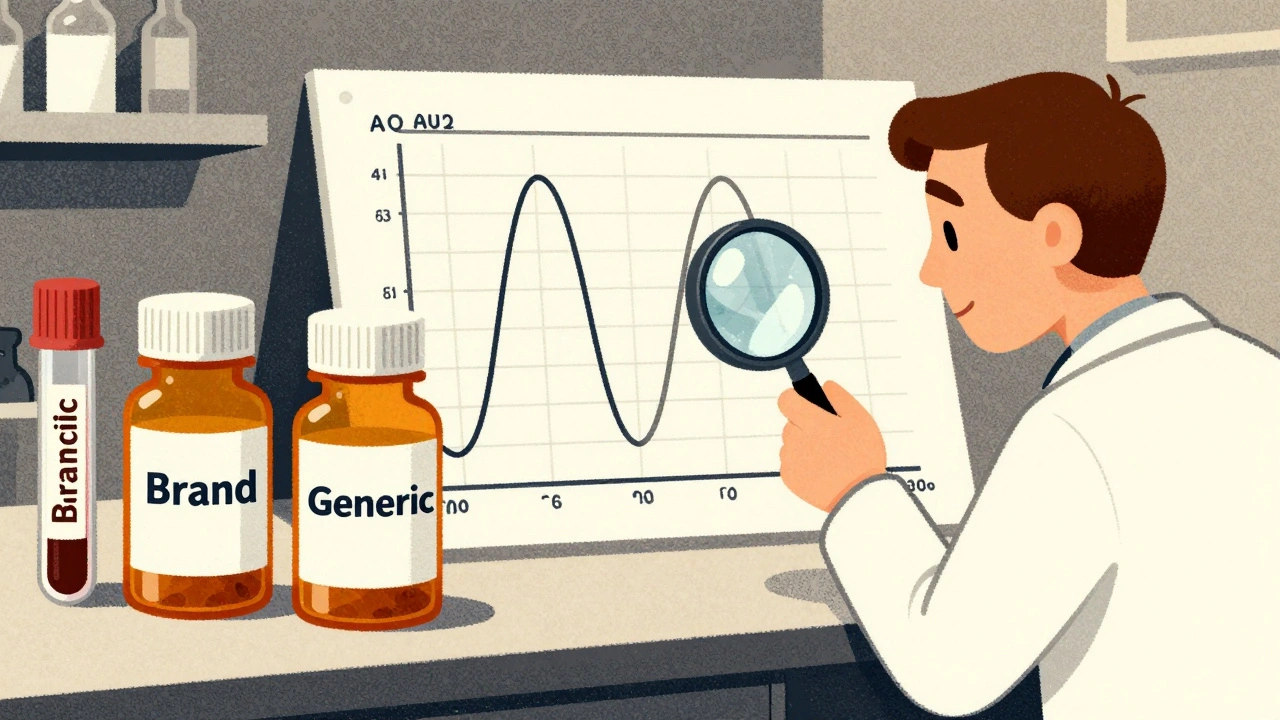

Two numbers tell the whole story: AUC and Cmax. AUC, or area under the curve, shows how much of the drug is in your blood over time. Cmax is the highest concentration reached. If a drug has low AUC, it’s not getting absorbed well. If Cmax is too high, you might get side effects. Too low, and it won’t work.

What Bioequivalence Is-and Why It Matters

Bioequivalence is the comparison game. It answers: Does this generic version act the same as the brand? It’s not enough for a generic to have the same active ingredient. It must deliver that ingredient at the same rate and to the same extent.

Here’s how regulators test it: healthy volunteers take both the brand and the generic, each in a separate period, with blood drawn every 30 minutes for 24 to 72 hours. The data from both are plotted, and the AUC and Cmax values are compared. The rule? The 90% confidence interval of the ratio between the generic and brand must fall between 80% and 125%. That’s the 80/125 rule.

That doesn’t mean the generic is exactly the same-it can be up to 20% weaker or stronger. But here’s the key: this range was chosen because it’s statistically proven to be safe. If two drugs are within this range, clinical outcomes are virtually identical. Studies show that over 99.7% of generics approved between 2010 and 2020 met this standard with no measurable difference in effectiveness or safety.

Think of it like two cars with the same engine. One might have a slightly different air filter or fuel line, but if both get you from A to B using the same amount of gas at the same speed, they’re functionally equivalent. Bioequivalence is the science behind that.

Why the Same Numbers Don’t Mean the Same Experience

Just because two drugs are bioequivalent doesn’t mean everyone feels the same. Take levothyroxine, used for hypothyroidism. It has a narrow therapeutic index-meaning small changes in dose can cause big effects. Even a 5% difference in absorption can make someone feel tired, anxious, or gain weight.

Some patients report switching from brand to generic and noticing a change. That’s not always because the generic failed the test. It could be because the brand was the first version their body got used to. Or because the generic has different fillers or coatings that affect how fast it dissolves. That’s why the FDA allows tighter limits for certain drugs: for warfarin, the AUC range is 90-112%, not 80-125%.

Pharmacists often see this. One study tracked 1,247 patients switched to generic blood pressure meds. Only 17 reported issues, and only 4 were confirmed as true bioequivalence problems. The rest? Stopped taking the meds, changed diets, or blamed the new pill for unrelated symptoms.

How Bioavailability Tests Are Done (And Why They’re So Strict)

Running a bioequivalence study isn’t simple. It requires:

- 24 to 36 healthy volunteers

- Randomized, crossover design (each person takes both drugs)

- Fasting conditions (no food to interfere)

- 12 to 18 blood draws over 72 hours

- Highly sensitive lab equipment to measure drug levels

It takes 3 to 6 months just to design and get approval for one study. And it’s expensive-often costing hundreds of thousands of dollars. That’s why only large generic manufacturers or contract labs can do it. But the payoff? Safe, affordable drugs for millions.

Some drugs are harder to test. Creams, inhalers, or injectables don’t show clear blood levels. For those, regulators use other methods-like measuring drug release in a lab dish (dissolution testing) or using computer models that simulate how the body absorbs it (PBPK modeling). The FDA is already moving toward these tools for complex generics.

What Happens When Bioequivalence Fails

It rarely does. But when it does, it’s serious. In the 1980s, a generic version of phenytoin (an anti-seizure drug) had slightly different fillers. The absorption rate changed enough to cause seizures in some patients. That’s why regulators tightened rules after that.

Today, if a generic fails bioequivalence, it’s rejected. No exceptions. Even small changes-like switching from lactose to cornstarch as a filler-require retesting. The FDA doesn’t approve generics based on theoretical similarity. They demand proof.

And the system works. In the U.S., 91% of prescriptions are filled with generics. Yet they make up only 22% of total drug spending. That’s billions saved every year-without a spike in hospitalizations or side effects.

What You Should Know as a Patient

You don’t need to understand AUC or Cmax. But you should know this:

- Generics are not cheaper because they’re weaker-they’re cheaper because they don’t need to redo clinical trials.

- Every generic you take has passed the same strict tests as the brand.

- If you feel different after switching, talk to your doctor. It’s not always the drug-it could be stress, sleep, or something else.

- For drugs like thyroid meds, blood thinners, or epilepsy treatments, stick with the same brand or generic unless your doctor says otherwise.

- Don’t assume all generics are identical. Different manufacturers use different fillers. If you’re stable on one, switching to another might cause a change-even if both meet bioequivalence standards.

The bottom line? Bioequivalence isn’t a loophole. It’s a rigorous, science-backed guarantee that your generic medicine will work just as well. And that’s why millions of people safely use generics every day.

Are generic drugs less effective than brand-name drugs?

No. Generic drugs must meet the same strict bioequivalence standards as brand-name drugs. They contain the same active ingredient, in the same strength, and must deliver it at the same rate and extent. Studies show that over 99% of approved generics perform identically to their brand counterparts in clinical outcomes.

Why do some people say they feel different on a generic?

Sometimes, it’s not the drug-it’s the mind. But real differences can happen with narrow therapeutic index drugs like levothyroxine or warfarin, where even small changes in absorption matter. Fillers, coatings, or dissolution rates can vary between manufacturers, even if both meet FDA standards. If you notice a change, talk to your doctor before switching back.

Is bioequivalence testing the same worldwide?

Yes, most major regulators-FDA, EMA, Health Canada, and others-use the same 80-125% range for bioequivalence. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) ensures global alignment. Some countries apply tighter limits for high-risk drugs, but the core standard is consistent across the U.S., Europe, Canada, Australia, and Japan.

Can I switch between different generic brands safely?

For most drugs, yes. But for medications with a narrow therapeutic index-like thyroid hormones, blood thinners, or seizure drugs-it’s best to stick with one manufacturer. Even though all generics meet bioequivalence standards, minor formulation differences can affect how your body responds. If you’re stable, don’t switch unless your doctor recommends it.

How long does it take to prove bioequivalence?

The actual study takes 2 to 3 months, but preparation takes much longer. Designing the protocol, getting ethics approval, recruiting volunteers, and analyzing data can take 6 to 9 months. Once approved, the generic can be sold. The entire process from development to market usually takes 1 to 2 years.

Do food and drink affect bioequivalence?

Yes. Some drugs absorb much better with food-like itraconazole or voriconazole. That’s why bioequivalence studies are done both fasting and after a high-fat meal. If food changes absorption significantly, the label will say to take the drug with food. This is built into the testing process to ensure safety in real-world use.

What’s Next for Bioequivalence?

The future is getting smarter. Instead of always testing in humans, regulators are starting to accept computer models that simulate how a drug behaves in the body-called PBPK modeling. This is already being used for complex drugs like topical creams and inhalers, where blood levels don’t tell the full story.

By 2027, experts predict that 30% of bioequivalence assessments for tricky generics will use these models to reduce the need for human trials. That means faster approvals, lower costs, and more access to affordable medicines.

But the core won’t change: safety first, science always. Whether it’s a new generic or a new brand, if it’s meant to go in your body, it must be proven to work the same way.

I switched my generic thyroid med last month and suddenly felt like a zombie who forgot to drink coffee. 😩 Like, I swear my brain was on 5% battery. My doctor said it’s ‘bioequivalent’-whatever that means-but my body says NOPE. Now I’m back on the brand. Worth every penny if I’m not gonna feel like I’m living in a slow-motion movie.

Look, the 80-125% rule is a joke. It’s not science-it’s corporate compromise. If you’re okay with a 20% swing in drug concentration, you’re basically gambling with your liver. I’ve seen people crash on generics. The FDA doesn’t care because Big Pharma profits more when you buy the cheap version. Wake up.

There’s a critical nuance here that gets lost: bioequivalence doesn’t mean bio-identical. The active ingredient is the same, yes-but excipients like lactose, cellulose, or magnesium stearate can alter dissolution kinetics, especially in patients with GI issues or motility disorders. That’s why levothyroxine is so finicky. The 80-125% range is statistically valid for population-level outcomes, but individual variability is real. For narrow therapeutic index drugs, consistency of manufacturer matters more than the generic/brand label.

Studies show that when patients are stabilized on one generic manufacturer and then switched to another (even if both meet FDA standards), up to 15% report subjective changes. Not always clinical, but enough to warrant caution. Pharmacies shouldn’t auto-substitute without patient consent for these meds.

One wonders if the entire regulatory framework is merely a modern myth-constructed to assuage public anxiety about cost-cutting in healthcare. The 80-125% rule, while mathematically elegant, is an arbitrary boundary drawn by bureaucrats who’ve never felt the tremor of a missed seizure or the fog of untreated hypothyroidism. Are we measuring drug levels… or the depth of our collective surrender to neoliberal efficiency?

Perhaps true equivalence isn’t in the bloodstream, but in the narrative we tell ourselves: that medicine is a product, not a covenant.

Y’all know what’s wild? I’ve been on the same generic blood pressure med for 8 years. Switched brands twice. Felt nothing. Zero. Nada. My BP’s stable, my energy’s good, I’m not dizzy. So maybe… just maybe… the ‘I feel different’ crowd is just projecting? Not saying it doesn’t happen-but don’t make it a universal truth because it happened to you once.

Also, generics saved my family $3K last year. I’ll take a 99.7% success rate over a $200 pill any day. 🙌

As someone who works in hospital pharmacy, I can tell you: the real issue isn’t bioequivalence-it’s pharmacy substitution without patient notification. Patients get switched from one generic to another every month, and they’re never told. That’s the hidden variable. The science is solid. The system? Broken. We need mandatory labeling of generic manufacturer on prescriptions. Period.

My uncle had a stroke after switching to generic warfarin. The pharmacy swapped it without telling us. He was fine on the brand. Then boom. Hospital. Now he’s on the brand again and stable. So don’t tell me generics are always fine. The system is lazy. The regulators are asleep. And the pharmacies? They don’t care as long as they get paid. This isn’t science-it’s capitalism with a stethoscope.

I just want someone to acknowledge how terrifying it is to be told your medicine is ‘equivalent’ when your body says otherwise. I’ve cried over pill bottles. I’ve Googled ‘why do I feel worse on generics’ at 3 a.m. I’m not crazy. I’m just a person who’s been failed by a system that reduces human experience to statistical ranges. I don’t need a graph. I need to feel like myself again.

There’s a reason why most doctors don’t push generics for thyroid, epilepsy, or anticoagulants. It’s not because they’re in the pocket of Big Pharma. It’s because they’ve seen patients destabilize after a switch-even when the numbers say it’s fine. Bioequivalence is a population-level tool. Human bodies aren’t populations. They’re individuals with unique metabolisms, gut flora, and histories. Treat them that way.

USA still lets generics pass with 20% variation? That’s insane. In China they test every batch. In Germany they require identical fillers. We’re letting corporations cut corners and calling it ‘science.’ This is why people don’t trust medicine anymore. We’re not protecting health-we’re protecting profit margins.

Oh wow so the 80-125 rule is ‘rigorous’? That’s like saying your car’s engine is ‘equivalent’ if it runs between 40% and 125% of its rated horsepower. I’d rather drive a horse.

It’s simple. If it works, don’t switch. If it doesn’t, talk to your doctor. No need for fancy terms. Just listen to your body. That’s all medicine really is-trying to help you feel better.

Let’s be real-the FDA approves generics based on data from 24 healthy young men. What about elderly women with kidney disease? Or people with Crohn’s? Or someone on 12 other meds? The system is designed to ignore real-world complexity. And now you’re telling me it’s ‘safe’? That’s not science. That’s propaganda.

It’s fascinating how we’ve built an entire regulatory edifice around a statistical tolerance that, in essence, allows for a 20% deviation in drug exposure. And yet we demand perfection in other areas-like food safety or airplane maintenance. Why is the human body treated as a variable to be averaged out rather than a system to be honored? Perhaps the real bioequivalence we need is between policy and human dignity.

My grandfather took the same generic statin for 12 years. Never had a problem. Never even knew it was generic. He lived to 94. Meanwhile, the brand version cost him $180/month. He’d have died sooner if he couldn’t afford it. So yeah, I’ll take the 99.7% chance of safety over the 100% chance of financial ruin.