When a child qualifies for Medicaid or CHIP, the government doesn’t just automatically enroll them. There’s a hidden gatekeeper: Medicaid substitution rules. These aren’t about denying care-they’re about making sure public funds aren’t used when private insurance is already available. But here’s the catch: every state handles them differently. Some use waiting periods. Others track insurance databases. A few have cracked the code and nearly eliminated coverage gaps. If you’re a parent, a caseworker, or just trying to understand why your kid got denied CHIP despite low income, this is what’s really going on.

Why These Rules Exist

The law is clear: Medicaid and CHIP are supposed to be the last resort. If a child has access to affordable private insurance through a parent’s job, public programs shouldn’t step in. This isn’t about punishing families-it’s about keeping private insurance markets stable and making sure taxpayer dollars go to those who truly have no other option. Back in 1997, Congress added this rule to prevent employers from dropping coverage because they knew Medicaid would pick up the slack. Fast forward to 2025, and the problem hasn’t gone away. In fact, it’s gotten more complex. With more gig work, short-term plans, and fluctuating hours, families move in and out of coverage faster than ever. Yet the rules were designed for a world where people held steady 9-to-5 jobs with predictable benefits.According to CMS, about 3.7 million children in CHIP programs are potentially subject to substitution checks. Without these rules, the federal government estimates public spending on children’s health would jump by $2.1 billion a year. That’s not a small number. But the cost of enforcing them? Also high. States spend an average of $487,000 annually just to verify private insurance. And for many families, the process feels like a maze.

The Mandatory Rule: No State Can Skip This

Every single state-plus DC-must follow one non-negotiable rule: CHIP cannot replace private coverage that’s affordable and available. This comes straight from Section 2102(b)(3)(C) of the Social Security Act. It’s not optional. If a parent has group health insurance through their employer that meets federal affordability standards (premiums under 9.12% of household income in 2024), the state must check before enrolling the child in CHIP.But how states do that? That’s where things get messy. The federal government doesn’t dictate the method. It just says: “You must prevent substitution.” So states got creative. Some built digital tools. Others stuck with paper forms and phone calls. The result? A patchwork of systems that leave families confused and caseworkers overwhelmed.

Optional Tools: Waiting Periods and More

States have a few optional tools they can use to enforce substitution rules. The most common? A waiting period. Federal law allows states to make families wait up to 90 days before enrolling in CHIP if they’ve lost private coverage. Thirty-four states use this approach. California, Texas, and New York-the three biggest states-rely on it heavily.But here’s what no one talks about: waiting periods don’t always work. A Medicaid worker in Ohio told a Reddit thread: “We get families who lose employer coverage on Friday and need CHIP Monday. But the 90-day rule forces us to deny them for 12 weeks. They often end up uninsured during that time.” That’s not a feature-it’s a flaw. Families fall through the cracks. Kids miss doctor visits. Emergency room visits spike. And in states like Louisiana, strict waiting periods actually caused the uninsured rate among low-income children to jump by nearly 5 percentage points in 2021.

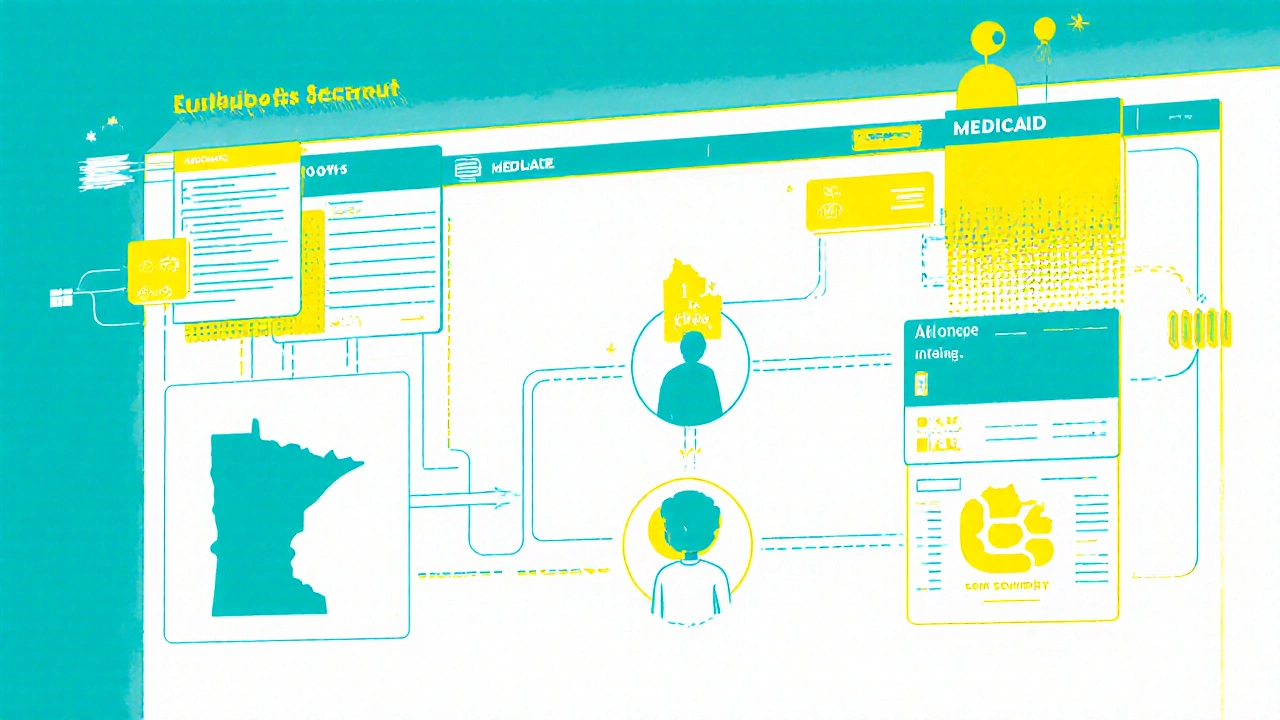

Then there are the 16 states that don’t use waiting periods at all. Instead, they rely on real-time data. They connect to private insurer databases to see if coverage is active. Twenty-eight states now use this method. It’s faster. More accurate. And it cuts down on gaps. Minnesota’s “Bridge Program” cut substitution-related coverage gaps by 63% using real-time matching. Massachusetts and Oregon followed suit. Their uninsured rates for eligible kids? Below 8%. That’s the gold standard.

What States Are Doing Right

The best-run programs don’t just block enrollment-they make transitions smooth. States with integrated Medicaid-CHIP systems (32 of them as of 2024) see 22% fewer coverage gaps than those with separate systems. Why? Because when a parent’s income changes or a job ends, the system automatically shifts the child from one program to the other. No forms. No delays. No denial letters.These states also have better verification tools. They don’t just ask families to prove insurance-they pull data directly from employers or insurers. They accept eligibility decisions from other programs like the Affordable Care Act marketplace. They train staff on nuanced cases: What if the employer offers insurance but the employee declined it? What if the plan is technically available but costs $600 a month? What if the parent works seasonal jobs and loses coverage every winter?

States like Minnesota and Oregon don’t just ask questions-they build systems that answer them automatically. That’s why they’re the outliers. Everyone else is still playing catch-up.

Where the System Fails Families

The biggest problem isn’t the rules-it’s the gaps between them. A 2022 CMS evaluation found that 21% of children still experience coverage gaps when switching between Medicaid and CHIP. That’s over 700,000 kids without insurance for weeks or months at a time. And it’s not random. It hits families with unstable jobs hardest: farmworkers, restaurant staff, retail workers, gig drivers. These are the people who lose coverage when their shift ends, their hours drop, or their employer switches health plans.Parents say the same thing over and over: “It’s too hard.” A 2023 Families USA survey found 42% of parents blamed bureaucratic delays related to substitution rules. Meanwhile, 31% said they appreciated the rules because they kept employers from dropping coverage. That split tells you everything. The system isn’t broken for everyone. But for those on the edge, it’s a wall.

And the paperwork? It’s brutal. A 2023 survey of 47 state Medicaid agencies found 68% listed “difficulty verifying private insurance” as their top challenge. Average processing time? 14.2 days. In that time, a child can miss a diabetes checkup, a vaccine, or a mental health appointment. That’s not policy-it’s harm.

The 2024 Rule Change: What’s Different Now

In March 2024, CMS rolled out a major update: the Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility and Enrollment rule. It didn’t remove substitution rules. It fixed their weakest parts. Now, states must:- Establish automatic transitions between Medicaid and CHIP when eligibility changes

- Accept eligibility determinations from other programs like the ACA marketplace

- Share data between programs in real time

- Start reporting quarterly metrics on coverage gaps and waiting period use

States have until October 1, 2025, to make the system changes. That’s not a lot of time. And it’s not easy. States with outdated tech will need 12 to 18 months to upgrade. Those with modern systems? They’re already ahead. The goal? Reduce those 21% coverage gaps to under 10%. If they succeed, it’ll be the biggest win for children’s health coverage since the ACA.

What’s Next for Medicaid Substitution Rules

By 2027, experts predict all states will use automated data matching. Manual verification will drop by 65%. That’s the trajectory. But it’s not guaranteed. The Congressional Budget Office says substitution rules will save $1.4 billion annually through 2030. The Urban Institute warns: if we don’t modernize, the rules will become useless. Why? Because the job market doesn’t look like it did in 1997. More people work multiple jobs. More employers offer junk plans that cost more than they’re worth. More families cycle in and out of coverage.Some experts, like Dr. Leighton Ku from George Washington University, say the 90-day waiting period is outdated. “It was designed for a world where people changed jobs once a year,” he told Congress in February 2024. “Now, people change coverage every few months.”

Others, like Joan Alker from Georgetown University, argue the rules punish working families for being employed. “It’s not a bug-it’s a feature of a system that assumes stability,” she says. “But for most low-income families, instability is the norm.”

The answer isn’t to scrap substitution rules. It’s to make them smarter. Faster. More human.

What You Can Do

If you’re a parent trying to get your child enrolled:- Ask if your state uses a waiting period. If yes, ask about exemptions-some states offer them for job loss or reduced hours.

- Don’t assume you’re ineligible just because your employer offers insurance. Ask if it’s affordable (under 9.12% of your income).

- Keep records of any job changes, pay stubs, or insurance cancellation notices. These can help speed up verification.

- If you’re denied, appeal. Many denials are mistakes.

If you’re a caseworker or advocate:

- Push for integrated systems. They’re the only thing that truly reduces gaps.

- Push for real-time data sharing. Paper forms are obsolete.

- Use the 2024 rule as leverage. It gives you tools to fix broken processes.

The goal isn’t to keep kids off Medicaid. It’s to make sure no kid falls through the cracks because of a system that was never meant for today’s economy. The tools exist. The data is there. The question is: who’s going to use them?

What is Medicaid substitution?

Medicaid substitution means preventing public health programs like Medicaid or CHIP from covering a child when they already have access to affordable private insurance through a parent’s employer. The goal is to preserve private insurance markets and direct public funds to those with no other options.

Are substitution rules the same in every state?

No. While all states must prevent substitution under federal law, they can choose how to do it. Thirty-four states use a waiting period of up to 90 days. Sixteen states rely on real-time data checks with private insurers. Some states add extra exemptions for job loss or reduced hours.

Why do some states deny CHIP enrollment even if a family has low income?

If a child has access to affordable private insurance through a parent’s job, federal rules require states to verify that coverage before enrolling them in CHIP. Even if the family has low income, they may be denied if private coverage meets affordability standards (premiums under 9.12% of household income in 2024).

What is the 90-day waiting period?

The 90-day waiting period is an optional tool states can use. If a family loses private insurance, they must wait up to 90 days before becoming eligible for CHIP. This is meant to prevent families from dropping coverage to get free public insurance. But critics say it leaves kids uninsured during critical times.

How has the 2024 rule changed substitution rules?

The March 2024 Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility and Enrollment rule requires states to automatically transition children between Medicaid and CHIP when eligibility changes, share data in real time, accept eligibility decisions from other programs, and report coverage gaps quarterly. These changes aim to reduce delays and gaps in coverage.

Which states have the best substitution systems?

Minnesota, Massachusetts, and Oregon have the most effective systems. They use real-time data matching between private insurers and public programs, which reduces coverage gaps to under 8%. These states also have integrated Medicaid-CHIP systems and automatic enrollment features.

Can I appeal a denial based on substitution rules?

Yes. If you’re denied CHIP because of substitution rules, you have the right to appeal. Many denials are based on outdated or incorrect insurance information. Keep documentation of job changes, insurance cancellations, and income statements to support your case.

Do substitution rules apply to adults on Medicaid?

No. Substitution rules only apply to children enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP under the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Adults on Medicaid are not subject to these rules, even if they have access to employer coverage.

This is such a mess. I work in child welfare and see families get denied CHIP every day just because their employer offers insurance that costs $700/month. They’re making $28k a year. That’s not affordable-it’s a trap. And then we have to tell them to wait 90 days? No wonder kids miss vaccines and end up in the ER. We need real-time data, not paper forms.

Minnesota’s system should be the national standard. Why are we still using 1997 logic in 2025?

The data is clear: substitution rules prevent moral hazard. Without them, employers would systematically offload coverage onto Medicaid. The $2.1B in potential savings isn’t hypothetical-it’s actuarial. The real issue isn’t the rules, it’s the implementation. States that cling to manual verification are failing their constituents, not the families.

Also, the 90-day waiting period is not a flaw-it’s a necessary buffer. It prevents gaming of the system. If you want faster access, fix the employer-side incentives, not the safety net.

There is a grammatical error in the post: ‘the federal government estimates public spending on children’s health would jump by $2.1 billion a year’ - should be ‘would jump by $2.1 billion annually.’ Also, ‘substitution rules’ is pluralized inconsistently in the header section. These are not minor issues-they undermine credibility. Precision matters in policy discourse.

Also, the term ‘junk plans’ is emotionally loaded and unprofessional. Use ‘non-compliant plans’ or ‘minimum essential coverage.’

I get what the system is trying to do, but it’s crushing real people. I’ve seen moms cry because their kid couldn’t get a doctor’s appointment for three months after losing their dad’s insurance. The system doesn’t care if you’re trying to do the right thing-it just checks boxes.

Real-time data isn’t fancy tech-it’s basic human decency. Minnesota’s system works because they treat families like humans, not cases. Let’s stop pretending this is about fiscal responsibility. It’s about compassion-or the lack of it.

And yeah, I’ve called my rep. We need to push for automatic transitions. It’s not hard. It’s just not prioritized.

Wait so you’re saying we should just give free health care to everyone who has a job? That’s insane. If your employer offers insurance you’re supposed to take it. That’s the whole point. Why should taxpayers pay for something you could’ve gotten for free?

Also the 90 day thing? That’s not a bug, that’s a feature. People need to learn responsibility. No one’s forcing you to work at a bad job. Get a better one.

And stop crying about paperwork. I filled out my taxes on paper in 1999. We survived.

Also typo: ‘substitution rules’ not ‘substition rules’ lol

Big respect to the states that are doing this right 🙌

Real-time data sharing? YES. Automatic transitions? YES. Reducing gaps? YES.

Minnesota, Oregon, Massachusetts-you’re the ones keeping kids alive. The rest of us are still stuck in the Stone Age with fax machines and PDFs. Let’s make this the new normal. No more excuses.

Also, if you’re a parent reading this: if you get denied, appeal. Seriously. I’ve seen 70% of denials get overturned on appeal. You’ve got rights. Use them. 💪

Let’s zoom out for a second. The entire structure of Medicaid and CHIP substitution was built on a 1997 economic model where 78% of workers had employer-sponsored insurance with predictable hours and stable employment. Today? Less than 52% do. Gig work, freelance contracts, seasonal labor, multiple part-time jobs-none of that fits into a 90-day waiting period or a manual verification process that takes 14 days.

What we’re really seeing isn’t a policy failure-it’s a structural obsolescence. The rules were designed for a world that no longer exists. And until we acknowledge that, we’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic. We need to stop trying to patch the system and start rebuilding it around the reality of modern work. That means automatic enrollment triggers, integrated eligibility engines, and eliminating the concept of ‘affordability’ as a static percentage. Because $600/month is never affordable if you’re making $18/hour and working 25 hours a week. The math doesn’t lie. The policy does.

And if you think this is just about money, you’re missing the bigger picture: every day a child goes without care, it costs society more in lost productivity, emergency visits, and long-term health outcomes. We’re paying for this delay. We just don’t see the invoice yet.

yo why is everyone making this so complicated 😅

if your job offers insurance you take it

if you lose it you wait 90 days

if you cant afford it you ask for help

its not rocket science

stop blaming the system its just doing its job

also typo in the title lol

substitution not substition

imagine writing a policy paper with typos 😂

THIS IS A NATIONAL EMERGENCY.

Children are DYING because of bureaucratic red tape.

90 DAYS. NINETY DAYS. That’s longer than a college semester. A kid with asthma can’t wait 90 days for a nebulizer.

States are playing politics with kids’ lives. And the people in charge? They’re sipping coffee in D.C. while parents are begging on Facebook for donations to pay for insulin.

This isn’t policy. This is cruelty wrapped in a spreadsheet.

And don’t give me that ‘moral hazard’ crap. You don’t get moral hazard when you’re working two jobs and still can’t afford your kid’s inhaler.

WE NEED TO DEFUND THE BUREAUCRACY AND INVEST IN HUMANITY.

AND IF YOU DISAGREE YOU’RE PART OF THE PROBLEM.

Real-time data works. End of story. Stop the waiting periods. Fix the system. Done.

One must interrogate the ontological assumptions underlying the substitution paradigm. The very notion of ‘affordability’ as a quantifiable metric presupposes a neoliberal framework wherein healthcare is commodified and familial responsibility is externalized. The 90-day waiting period functions not as a policy tool but as a disciplinary mechanism, reinforcing the myth of individual agency in a structural landscape of precarity.

It is not the system that is broken-it is the epistemology that permits such a system to persist. To advocate for real-time data without addressing the underlying ideological architecture is to rearrange the furniture in a burning house.

And yet, paradoxically, the 2024 rule change represents a Hegelian synthesis: the thesis of fiscal restraint, the antithesis of access, and the synthesis of automated equity. Whether this synthesis will endure remains contingent upon the dialectical material conditions of state capacity.

One must ask: who is the subject of this policy? The child? The parent? The insurer? The state? Or merely the algorithm?