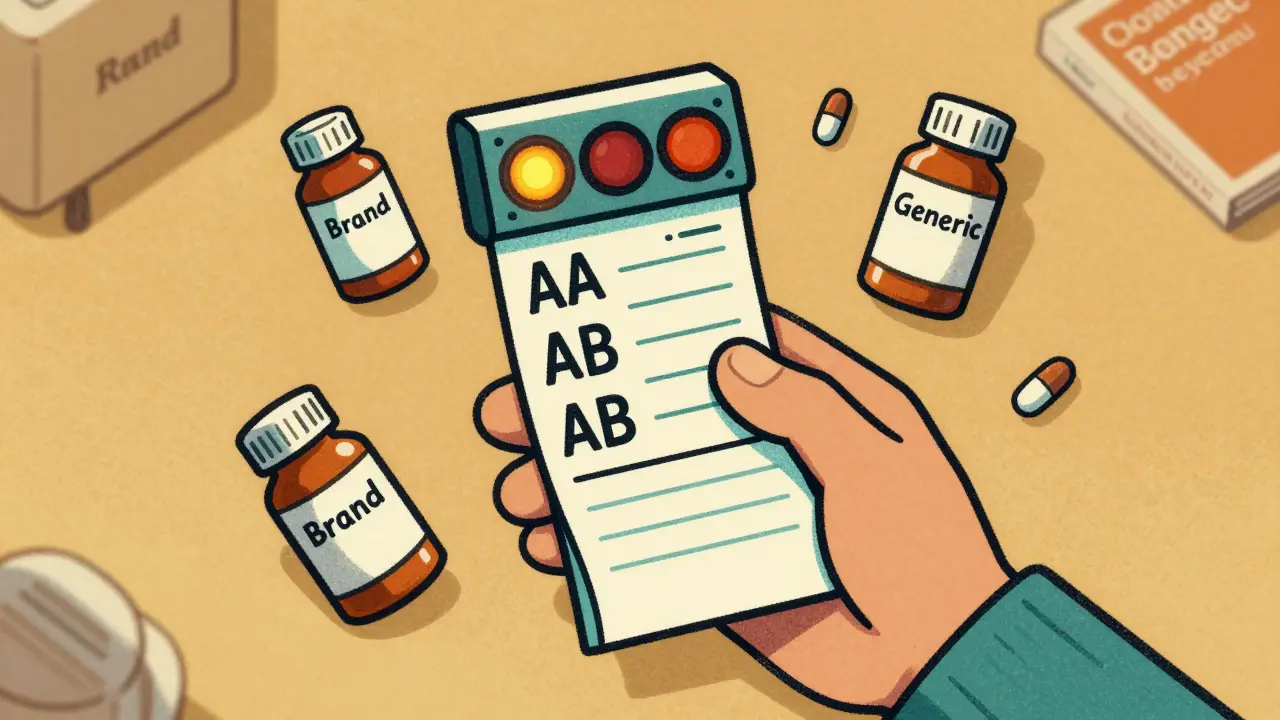

When you pick up a prescription, you might not notice the little letters next to the drug name on your receipt-like AA or AB or even BT. But those codes? They’re the legal gatekeepers that decide whether your pharmacist can swap your brand-name drug for a cheaper generic. This isn’t just a pharmacy policy. It’s federal law, backed by science, and enforced state by state. If you’ve ever wondered why some generics are interchangeable and others aren’t, the answer lies in the FDA’s Therapeutic Equivalency (TE) Codes-and how U.S. pharmacy laws tie directly to them.

What Are FDA Therapeutic Equivalency Codes?

The FDA assigns TE codes to prescription drugs listed in the Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, better known as the Orange Book. This isn’t a marketing tool or a suggestion. It’s the official, legally recognized database that tells pharmacists, doctors, and regulators: Can this generic be swapped for the brand without risk? The system started in 1980, but it was the Hatch-Waxman Amendments of 1984 that turned it into the backbone of generic drug substitution in the U.S. Before that, generic manufacturers had to run full clinical trials to prove their drugs worked. Hatch-Waxman changed that. It allowed generics to prove they were bioequivalent-meaning they delivered the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate-as the brand-name drug, called the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). That cut development costs and opened the door for affordable alternatives.But bioequivalence alone isn’t enough. Two drugs can have the same active ingredient and the same blood levels, but if one is an extended-release tablet and the other is a quick-dissolve capsule, they’re not interchangeable. That’s where TE codes come in. They combine three things: pharmaceutical equivalence (same ingredients, strength, form), proven bioequivalence, and identical safety and effectiveness under labeled conditions.

The Letter System: What AA, AB, and B Mean

TE codes use a simple but powerful two-character system. The first letter tells you the big picture. The second adds detail.- A = Therapeutically equivalent. This is the green light. Your pharmacist can substitute this generic without asking your doctor. About 62% of all listed drugs in the Orange Book have an A rating.

- B = Not equivalent. These are the red flags. They might have issues with absorption, delivery, or inconsistent performance. Don’t assume you can swap these.

The second letter gets specific:

- AA: Immediate-release oral drugs with no bioequivalence concerns. The most common and safest to swap.

- AB: These started as B-rated but were later proven equivalent after more testing. Still safe to substitute.

- BT: Topical products (creams, ointments) with bioequivalence issues. Hard to measure how much gets into the skin. Pharmacists often avoid swapping these.

- BN: Nebulized aerosols. Delivery depends on device design, not just the drug. Even if the chemical is the same, the inhaler might not deliver the same dose.

- BC: Extended-release tablets with unresolved bioequivalence data. These are tricky. Swapping them could mean uneven dosing over time.

- BX: Not enough data to rate. The FDA doesn’t know if they’re equivalent. Don’t substitute.

For example, two different brands of metformin 500mg tablets might both be rated AA. But if one is a generic version of a brand with a special coating, and the coating affects how fast the drug releases, it might get an AB or even a B. That’s why two generics of the same drug can have different codes.

How State Laws Turn FDA Codes Into Action

The FDA sets the science. But states set the law. Every state requires pharmacists to check the Orange Book before substituting a brand with a generic. If the code isn’t A, substitution is illegal in most places.Take California. Its Business and Professions Code Section 4073 says: “A pharmacist may substitute only if the drug product is rated as therapeutically equivalent.” No A code? No swap. Same in New York, where the Office of the Professions mandates that pharmacists consult the current Orange Book edition before substituting. Even in states with more flexible substitution laws, the Orange Book is still the legal baseline.

That means if your prescription says “Lipitor 20mg” and the pharmacy has a generic with an AB rating, they can swap it. But if the generic has a BT rating (like a topical cholesterol cream), they can’t. Even if it’s cheaper. Even if the doctor didn’t say “do not substitute.” The law says no.

Why Some Drugs Still Have B Codes

You might wonder: If the FDA approves a generic, why isn’t it always interchangeable? The answer lies in complexity.Simple pills? Easy. Bioequivalence is measured in blood tests. But what about:

- A cream that needs to penetrate skin layers evenly?

- An inhaler that depends on the device’s nozzle and pressure?

- An extended-release tablet that slowly dissolves over 12 hours?

These are hard to test. Traditional blood-level tests don’t always capture how the drug behaves in the body. A generic might have the same active ingredient, but if the inactive ingredients change how it’s absorbed-or if the delivery device differs-it can affect outcomes.

That’s why 24.3% of FDA-approved drugs still carry B codes. And why 68% of pharmacists surveyed in 2022 said they hesitate to substitute topical (BT) or nebulized (BN) generics-even when FDA-approved. It’s not about distrust. It’s about uncertainty.

The FDA knows this. In 2023, they launched the Complex Generic Drug Initiative to reduce the B-code backlog. They’ve already cut review times for complex generics from 34 months in 2018 to 22 months in 2023. And they’ve allocated $28.7 million through GDUFA III to develop better testing methods.

What This Means for You as a Patient

If you’re on a generic drug, here’s what you should know:- Most generics you get are AA or AB. You’re safe. These account for over 94% of all generic prescriptions.

- Don’t assume all generics are equal. If your prescription switches to a different generic, ask your pharmacist: “Is this rated the same as the last one?”

- If your drug has a B code, your pharmacist can’t substitute it. If you’re being charged more for a brand, ask why. You might be paying extra for no reason.

- Always check your receipt. The TE code isn’t printed, but the generic name is. If you see the same generic name every time, you’re likely getting the same product. If it changes, ask.

And if your doctor writes “dispense as written” or “no substitution,” that’s their choice. But if they don’t, the law lets the pharmacist choose-only if the code says it’s safe.

The Big Picture: Savings, Science, and Safety

The TE code system isn’t just about rules. It’s about saving money without risking health.Since 1995, generic drugs approved under this system have saved the U.S. healthcare system over $1.7 trillion. In 2022 alone, A-rated generics saved $298 billion. That’s money that goes back into hospitals, research, and patient care.

But the system isn’t perfect. In 2022, the FDA received 1,247 citizen petitions challenging TE codes-mostly from brand-name companies trying to block generic competition. That’s up 17% from the year before. It shows the system works, and it’s under pressure.

By 2027, the FDA aims to reduce B-code products from 24.3% to under 15%. That means more generics will become interchangeable. More savings. More access.

The bottom line? The TE code system is one of the most successful public health tools ever created. It balances innovation, competition, and safety. And it’s why you can get a month’s supply of blood pressure medicine for $4 instead of $400.

What’s Next for Therapeutic Equivalency?

The Orange Book went fully digital in January 2023. Now, electronic health records can pull TE codes directly into pharmacy systems. That means fewer errors. Faster checks. Better decisions.The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance on complex products is a game-changer. It outlines new ways to prove equivalence for inhalers, patches, and injectables-using not just blood tests, but real-world performance data. That could turn dozens of B-rated drugs into A-rated ones in the next few years.

For patients, that means more affordable options. For pharmacists, clearer rules. For the system, more trust.

Therapeutic equivalency isn’t about cutting corners. It’s about proving that a cheaper pill can do the same job as an expensive one-safely, reliably, and consistently. And the law makes sure it’s done right.

Wow, I had no idea those little letters on my receipt meant so much! 🤯 So my generic blood pressure med is AA? That’s a relief. I thought they were just random codes. Thanks for explaining this like I’m not a pharmacist 😊

I hate when they switch my meds without telling me. Last month I got a different generic and I felt like crap for a week. They didn’t even tell me the code changed. This is why I’m never trusting pharmacies again.

This is actually one of the most well-explained breakdowns of the Orange Book I’ve seen. The distinction between AA and AB is crucial - I’ve seen pharmacists get confused even though they’re both A-rated. The real issue is that most patients don’t know to check the generic name on the bottle. If it changes, ask. Simple as that. Also, BT codes for topical stuff? Yeah, that’s a mess. I’ve seen people get rashes from switching creams. It’s not just about blood levels.

62% A-rated? That’s a lie. I checked the FDA’s latest data dump. It’s actually 58.3%. And the 94% stat? That’s only true for oral solids. For inhalers, it’s under 30%. You’re cherry-picking numbers to make the system look better than it is.

In India we dont have this system but i read this and think wow america really care about safety even for cheap medicine. Respect 🙏

This is why America still leads. Other countries just let any junk be called a generic. We have science. We have law. We don’t let some foreign factory slap a label on a pill and call it the same. You think Canada or Germany checks this? Nah. They just trust the label. We actually make sure it works. That’s why our healthcare is better.

This post gave me chills. 💪 Seriously - $298 billion saved in 2022? That’s not just a number. That’s a grandma keeping her insulin. That’s a kid getting asthma meds instead of skipping school. That’s the system working the way it should. The FDA’s Complex Generic Initiative? That’s the future. More A-ratings = more people treated. More dignity. More life. Keep fighting for this stuff. 🙌

You say the TE system is a public health triumph. But let’s be real - it’s a corporate compromise. Hatch-Waxman didn’t create competition. It created a monopoly for generics with low barriers to entry. The real winners? Big pharma that patents the delivery system, then lets generics copy the active ingredient while they keep charging for the original device. The FDA doesn’t have the tools to measure real-world outcomes for complex drugs. So they guess. And we pay for it. This isn’t science. It’s legal fiction dressed up as safety.

In my country, generics are sold without any code system. People get sick because the absorption is different. Your system is not perfect, but at least you try to measure it. That’s more than most do. I hope your FDA keeps improving the testing. We need this everywhere.