After an organ transplant, survival isn’t just about the surgery. It’s about the daily battle to keep your new organ alive while your body tries to reject it. That’s where immunosuppressant drugs come in - powerful medications that silence your immune system so it doesn’t attack the transplanted kidney, liver, heart, or lung. But these lifesaving drugs don’t come without consequences. They change how your body works, interact with everything else you take, and can cause side effects that last for years - even decades.

How Immunosuppressants Work and Why They’re Necessary

Your immune system is designed to find and destroy foreign invaders - viruses, bacteria, and yes, even transplanted organs. Without drugs to suppress it, your body would treat the new organ like an enemy. That’s why transplant recipients need to take immunosuppressants for life. There’s no such thing as a natural tolerance to a donor organ, except in rare cases like identical twins.

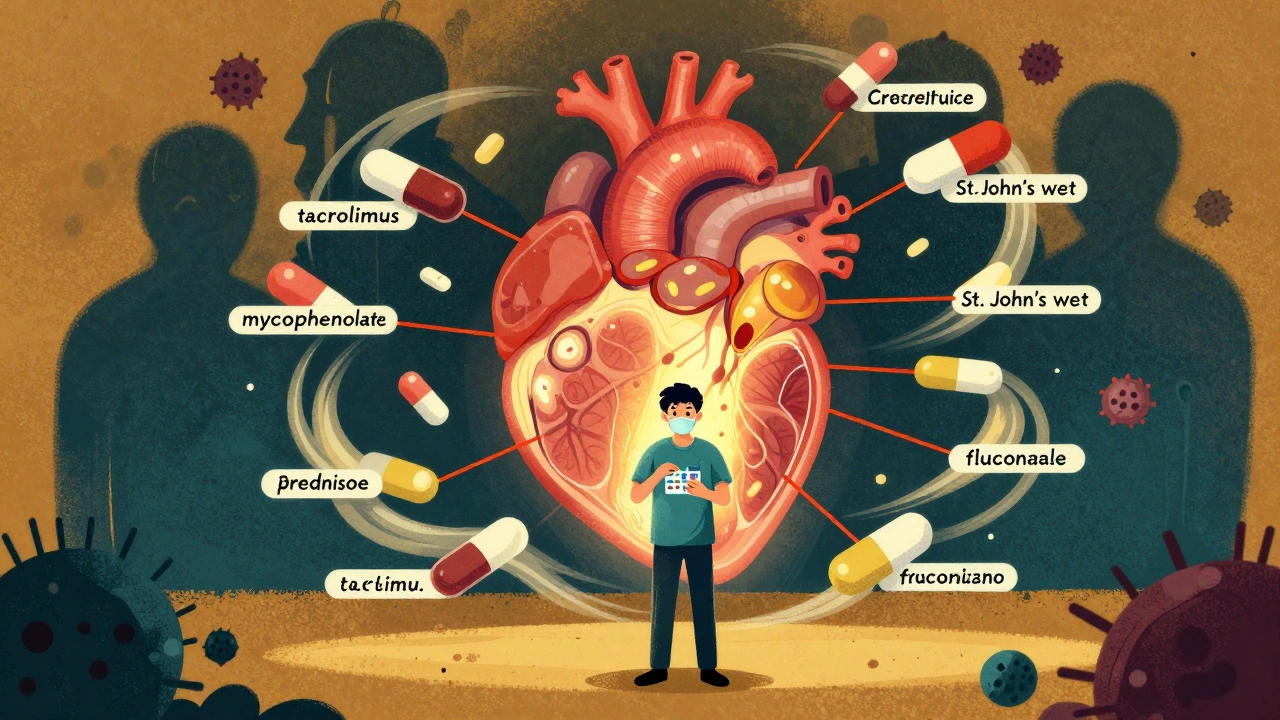

Most patients take a combination of three drugs: a calcineurin inhibitor (like tacrolimus or cyclosporine), an antimetabolite (like mycophenolate or azathioprine), and a corticosteroid (like prednisone). This triple therapy reduces the chance of rejection by targeting different parts of the immune system. Tacrolimus is the most common calcineurin inhibitor used in the U.S., taken by over 90% of kidney transplant patients because it’s more effective than cyclosporine at preventing rejection.

But here’s the catch: these drugs have a very narrow window between working and causing harm. Too little, and your body rejects the organ. Too much, and you’re at risk for serious infections, organ damage, or cancer. That’s why blood levels are monitored closely - sometimes twice a week in the first months after transplant.

Common Drug Interactions That Can Be Dangerous

Immunosuppressants don’t live in isolation. They’re processed by your liver using enzymes called CYP3A4 and moved around your body by a protein called P-glycoprotein. That means almost any other medication, supplement, or even food can mess with how they work.

For example, common antifungal pills like fluconazole (used for yeast infections) can cause tacrolimus levels to spike by 50% to 200%. That can lead to kidney damage or neurological problems like tremors and headaches. On the flip side, the antibiotic rifampin can drop tacrolimus levels by 60% to 90%, putting you at immediate risk of rejection.

Even over-the-counter stuff matters. St. John’s wort, a popular herbal remedy for mild depression, can reduce tacrolimus levels by up to 50%. Grapefruit juice? It blocks the same liver enzyme that breaks down tacrolimus, so just one glass can cause dangerous buildup. Many patients don’t realize this until they get sick.

Antibiotics, antivirals, blood pressure meds, cholesterol drugs, and even some acid reflux pills can interact. That’s why every new prescription - even a simple antibiotic for a sinus infection - must be reviewed by your transplant team before you start it. A 2020 study found that 30% to 40% of commonly prescribed drugs have significant interactions with calcineurin inhibitors. That’s nearly half of all meds you might be given.

Side Effects You Can’t Ignore

Side effects aren’t just annoying - they’re life-altering. And they don’t go away after the first year.

Nephrotoxicity - kidney damage - is the most common side effect of calcineurin inhibitors. Up to 40% of kidney transplant patients develop chronic damage visible on biopsies by year five. This isn’t just a lab number. It means your new kidney slowly loses function over time, sometimes requiring a second transplant.

New-onset diabetes after transplant (NODAT) affects 20% to 30% of patients on tacrolimus, compared to 10% to 15% on cyclosporine. That means you’re now managing two chronic conditions: transplant rejection and blood sugar control. Many patients report needing insulin or oral diabetes meds within months of starting tacrolimus.

Gastrointestinal issues are rampant with mycophenolate. Up to half of patients get diarrhea, nausea, or stomach pain. Some can’t eat normally. Others lose weight or can’t work because they’re constantly in the bathroom. Azathioprine causes fewer stomach problems but increases the risk of low white blood cell counts, making infections more likely.

Corticosteroids like prednisone are the worst offenders for long-term damage. Forty to sixty percent of transplant recipients develop osteoporosis - weak, brittle bones that break easily. One in three will have a fracture by year ten. Steroids also cause weight gain (15 to 20 pounds in the first six months), facial swelling ("moon face"), fat deposits on the back of the neck ("buffalo hump"), and mood swings. Many patients say they don’t recognize themselves in the mirror.

Malignancy risk is real. Skin cancer is the most common - 23% of liver transplant patients develop nonmelanoma skin cancers. Other cancers - like lymphoma, lung, colon, and HPV-related cancers - occur at rates up to 100 times higher than in the general population. That’s why annual skin checks and cancer screenings are non-negotiable.

What Patients Are Really Experiencing

Behind the statistics are real people living with these side effects every day.

One Reddit user, u/KidneyWarrior, describes tremors from tacrolimus so bad he couldn’t hold a coffee cup. Another, u/LiverSurvivor, switched from tacrolimus to sirolimus after his kidney function dropped. His GFR improved from 38 to 52 - a big win - but now he deals with mouth ulcers and high cholesterol requiring statins.

A survey from the National Kidney Foundation found 85% of transplant recipients get more infections than before. Seventy-two percent report chronic fatigue. Sixty-eight percent struggle with sleep. Fifty-four percent say they feel emotionally unstable - angry one minute, crying the next. These aren’t "minor" side effects. They’re daily battles that affect jobs, relationships, and self-image.

One woman in New Zealand shared how she avoided mirrors for months after her transplant because of her swollen face. Another said she couldn’t hug her grandchildren for fear of catching a cold that could kill her.

Managing the Balancing Act

There’s no perfect solution - only better management. Most transplant centers require patients to take 8 to 12 pills a day at specific times. Missing a dose or taking it at the wrong time can trigger rejection. That’s why electronic pill dispensers with alarms have improved adherence from 72% to 89% in some programs.

Monitoring is constant: monthly blood counts to check for low white cells, quarterly lipid panels because cholesterol spikes in 60% to 70% of patients, and biannual glucose tests to catch diabetes early. Blood levels of tacrolimus are tracked for life - sometimes every month after the first year.

Patients are told to avoid raw meat, unpasteurized cheese, and sushi to prevent Listeria. They’re advised to wear masks in crowded places, especially during flu season. Any fever over 100.4°F (38°C) must be reported immediately - it could be the first sign of a life-threatening infection.

Most centers require patients to live within two hours of the transplant hospital for the first year. That’s so they can get emergency care if rejection happens. Ninety-two percent of U.S. programs enforce this rule.

New Hope on the Horizon

There’s progress. In 2023, the FDA approved voclosporin - a new calcineurin inhibitor that causes 24% less kidney damage than tacrolimus. In 2024, data showed belatacept, a different kind of immunosuppressant, cuts heart disease and cancer risk by 25% to 30% compared to tacrolimus over seven years.

Some centers now use steroid-free protocols for low-risk patients, withdrawing prednisone within two weeks of transplant. This reduces bone loss, weight gain, and diabetes risk by 35% to 40%.

The most exciting research is in immune tolerance. The ONE Study found that 15% of kidney transplant recipients could stop all immunosuppressants after receiving regulatory T-cell therapy - their bodies learned to accept the new organ. That’s still experimental, but it’s the first real step toward a future where transplant patients don’t need lifelong drugs.

What You Need to Do Now

If you’re on immunosuppressants:

- Never start a new medication - even vitamins or herbal supplements - without talking to your transplant team.

- Keep a written list of every drug you take, including dosages and times.

- Report any new symptom immediately - even if it seems small.

- Attend all lab appointments and follow-up visits. Skipping one can cost you your graft.

- Use pill organizers with alarms. Adherence saves lives.

- Get annual skin checks and cancer screenings. Don’t wait for symptoms.

- Ask about steroid minimization if you’re on prednisone long-term.

There’s no easy path after a transplant. But understanding these drugs - their power, their risks, and how to manage them - gives you control. You’re not just surviving. You’re learning to live with a new normal. And that’s worth fighting for.

Can I take over-the-counter pain relievers after a transplant?

You can take acetaminophen (Tylenol) for mild pain, but avoid NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen. These drugs can damage your new kidney, especially when combined with calcineurin inhibitors. Always check with your transplant team before taking any OTC medicine, even if it seems harmless.

Why do I need to avoid grapefruit juice?

Grapefruit juice blocks the liver enzyme CYP3A4, which breaks down tacrolimus and cyclosporine. This causes the drug to build up in your blood to dangerous levels, increasing the risk of kidney damage, tremors, and nerve problems. Even one glass can have an effect that lasts days. Switch to orange juice or water instead.

Can I ever stop taking immunosuppressants?

For almost all transplant recipients, no - immunosuppressants are lifelong. There are rare cases where experimental therapies like regulatory T-cell treatment have allowed patients to stop drugs safely, but this is only available in clinical trials. Stopping your meds on your own almost always leads to organ rejection and can be fatal.

How do I know if my immunosuppressant levels are too high or too low?

You won’t feel it directly. That’s why regular blood tests are critical. High tacrolimus levels may cause tremors, headaches, or kidney damage. Low levels can lead to rejection without symptoms at first - until your organ starts failing. Your transplant team uses blood tests, not symptoms, to adjust your dose.

Is it safe to get vaccinated while on immunosuppressants?

Yes - but only certain vaccines. You should get inactivated vaccines like flu, pneumonia, and COVID-19 shots. Avoid live vaccines like MMR, chickenpox, or nasal flu spray. Your immune system can’t handle them, and they could make you sick. Always check with your transplant team before getting any vaccine.

What should I do if I miss a dose of my immunosuppressant?

If you miss a dose, take it as soon as you remember - unless it’s close to your next scheduled dose. Never double up. Call your transplant center immediately for advice. Missing doses increases your risk of rejection, even if you feel fine. Keep a backup supply and set phone alarms to avoid this.

Do immunosuppressants cause weight gain?

Yes - mainly because of corticosteroids like prednisone. These drugs increase appetite, cause fluid retention, and change how your body stores fat. Most patients gain 15 to 20 pounds in the first six months. Diet and exercise help, but the drugs themselves make weight loss harder. Talk to your team about steroid-sparing protocols if this is a major concern.

Are there cheaper alternatives to brand-name immunosuppressants?

Yes. Generic versions of cyclosporine (Gengraf) and mycophenolate (Myfortic) are available and cost 25% to 30% less. Tacrolimus generics are expected to become available in 2025 after patent expiration. Always confirm with your pharmacist and transplant team that the generic is bioequivalent and approved for transplant patients.

Just got my kidney transplant last year and let me tell you - grapefruit juice is now public enemy #1. I switched to orange juice and my tacrolimus levels finally stabilized. No more tremors, no more headaches. Simple swap, massive difference.

It’s wild how much the medical system overlooks the daily grind of post-transplant life. I’ve been on tacrolimus for 11 years and the side effects are a slow erosion - weight gain, brittle bones, constant fear of infection. You’re not just managing a disease, you’re managing a new identity. The fatigue isn’t just tiredness - it’s a deep, cellular exhaustion that no amount of sleep fixes. And the meds? They don’t just interact with drugs - they interact with your dreams, your relationships, your sense of self. Most people think you’re ‘lucky’ to have a new organ. They don’t see the price tag.

For anyone new to this: keep a physical notebook. Write down every med, every supplement, every weird symptom. I lost my job because I didn’t track my prednisone dose and ended up with a steroid-induced psychosis episode. Your transplant team isn’t mind-readers. You have to be your own advocate. Also - yes, you can still hug your grandkids. Just wash your hands first. And don’t let anyone make you feel guilty for needing to say no to gatherings. Your life matters more than their expectations.

Let’s be real - the whole transplant industry is a money machine. Why do you think they push these lifelong drugs? Because they make billions. There’s no cure because a cure doesn’t pay. Steroid-free protocols? Sure, they exist - but only for the ‘low-risk’ patients who already have insurance and access to top-tier care. The rest of us? We’re guinea pigs on a drug treadmill. And don’t even get me started on how they profit off the fear of rejection. It’s not medicine - it’s a business model built on dependency.

Ever wonder why the FDA approves these drugs so fast? Big Pharma owns them. The ‘new’ drugs like voclosporin? They’re just repackaged old ones with a new patent. And don’t believe the hype about ‘immune tolerance’ - it’s a distraction. If they really wanted to cure rejection, they’d invest in regenerative medicine, not tweak existing immunosuppressants. They don’t want you cured. They want you compliant. And those pill organizers? They’re not helping you survive - they’re keeping you hooked. Read the clinical trial disclosures. You’ll see the real side effect: corporate greed.

Anyone who thinks this is just about ‘taking pills’ clearly hasn’t lived it. You’re not just managing a drug regimen - you’re managing a psychological prison. The constant blood tests, the fear of a fever, the way your own body betrays you - it’s not resilience. It’s survival on autopilot. And let’s not pretend the ‘new hope’ drugs are revolutionary. Belatacept? Still a calcineurin alternative. Still toxic. Still expensive. Still controlled by the same corporations. This isn’t progress. It’s rebranding.

My mom got a liver transplant in 2012. She’s been on tacrolimus since. She developed diabetes, lost her hair, gained 40 pounds, and now has to take 14 pills a day. She says she’d do it again - but she also says she wishes someone had warned her how much of her life would vanish. The ‘new normal’ isn’t normal. It’s a life reduced to lab ranges and pharmacy runs. And the worst part? No one talks about the grief. You don’t just lose your old body - you lose the person you were before the transplant. The ‘survivor’ label feels like a lie sometimes.

Here’s the truth no one wants to say: most transplant patients are just delaying death. The drugs are toxic. The side effects are brutal. The cancer risk? It’s not a ‘slight increase’ - it’s a ticking clock. And don’t tell me about ‘quality of life’ - when you’re too tired to shower, too scared to leave the house, and your skin is covered in pre-cancerous lesions - that’s not living. That’s waiting. And the system? It celebrates you as a ‘miracle’ while quietly counting your pills and your future hospital bills.

Look - if you’re taking immunosuppressants, you’re basically a walking biohazard. You can’t eat raw food, you can’t go to concerts, you can’t even get a flu shot without a 30-minute consultation. And yet, people still ask if you’re ‘over it.’ 😒 Like it’s a bad haircut. I’ve had 7 infections since my transplant. 7. And I’m supposed to be grateful? I’m not a hero. I’m a statistic with a pill schedule. And if you think generic meds are safe? Try switching from brand-name tacrolimus to a generic and then explain to your doctor why your levels spiked 40% and you nearly lost your kidney. 🤦♂️

From a clinical perspective, the CYP3A4/P-gp interaction profile is one of the most complex in pharmacotherapy. The narrow therapeutic index of calcineurin inhibitors demands precision - which is why therapeutic drug monitoring is non-negotiable. What’s often underappreciated is the pharmacokinetic variability between individuals - influenced by genetics, gut microbiome, even circadian rhythm. This isn’t just ‘take a pill’ medicine. It’s precision medicine with zero margin for error. And yes - grapefruit juice? It’s a CYP3A4 inhibitor. One glass = 72-hour effect. That’s not folklore. That’s pharmacology.

You’re not alone. I’ve been on this ride for 8 years. Some days are hell - but I still go hiking, I still bake cookies, I still dance in my kitchen. The meds are hard, but they’re not the whole story. Find your people - online, in support groups, in your clinic. And don’t let anyone make you feel guilty for needing rest, for crying, for being angry. This isn’t a race. It’s a marathon with no finish line. But you’re still running. And that’s strength.

One thing I wish I knew earlier: your body adapts. The tremors from tacrolimus? They faded after 6 months. The weight gain? I lost it with a low-carb diet and walking 10k steps a day. The fear? It lessens - not because you’re not scared, but because you learn how to live with it. Don’t compare your year 1 to someone’s year 10. You’re not behind. You’re learning. And if you’re reading this - you’re already doing better than you think.

So you’re telling me I can’t have a glass of grapefruit juice… but I can have 12 different prescription drugs that probably cause cancer? Sounds like a fair trade. 🙄